Sold out

Mirror of civilisation

drs Hélène J. Bremer, art historian and curator

Brightening up castles. Muffling sound. Excluding draught. Portraying mythological and historical tales. Status symbol. Just a few thoughts that come up when I think of historic tapestries. It is quite a thing to feel at home with such notions as an artist and continue the centuries-old tradition of weaving and making tapestries, all the more when you realize that many representations in history were made after the design of the great masters of painting. But this has not prevented Jenny Ymker from taking the main function of tapestries, telling stories, into the 21st century.

The stories on Jenny Ymker’s tapestries are topical, connected to time and place. In the 15th and 16th centuries tapestries were part of a travelling household. Monarchs and wealthy noblemen travelled from one medieval castle to the next or put up their tents during a battle. The tapestries were used as a protection against the cold of the damp castle walls or to stop the wind, but above all they were household goods, luxurious items of prestige like jewels and golden objects. They were used to show off. The images were based on various sources: from ancient history, chivalric romances and battles to scenes form daily life of both nobility and peasants, but Biblical and moralizing subjects were used as well. These images give insight into the times, and thanks to the large surface area of tapestries, many details could be included on them; for this reason, tapestries are also called ‘mirrors of civilization’: a feast for the eyes, now as then. An example.

On the 16th-century tapestry in Ammersoyen castle, described as a ‘Landscape verdure with hunting and rural scenes’ (figure 1) the central image features a hilly forest landscape in which a hunting scene and the harvest are pictured. But there is so much more to be seen. Several groups of people are caught up in various activities. The main image is surrounded by a margin with various objects including vases with flowers, columns with sphinxes on them, mythological figures and children playing. In turn, this strip with figures is decorated by a narrow band on the edges, featuring stylized flowers and clover leaves. It is worth observing and interpreting.1

During the Renaissance, tapestries were valued higher artistically. From the moment the famous painter Raphael started making designs and, later, Peter Paul Rubens designed the so-called cartoons for the tapestries for the rich and famous of their times, owning a tapestry became even more prestigious. All over Europe, large centres for tapestry weaving emerged, with one deserving of particular mention: that of Gobelins in Paris. For her work Jenny also uses the term Gobelin, but in fact the only tapestries deserving of the name are the ones woven in the Manufacture des Gobelins, founded by Louis XV. This may be historically correct, but in the Netherlands the terms Gobelin and tapestry are interchangeable.

In the 18th century the interest in tapestries decreased due to the emergence of much cheaper wallpaper, and it was not until the early twentieth century that interest for the technique and craftsmanship of tapestries made a comeback. The craft of weaving has not changed much over the ages. Early in history, the simple weaving frame made way for the loom on which the warp threads could be fixed and subsequently moved up and down to create space for the weft, or filling yarn. The warp is nearly always made of strong material such as wool, the weft may be of wool, linen or, for instance, silk. Mechanization has given weaving a totally different dimension, but fortunately there is still room for weaving mills that keep this technique alive using traditional methods.2 The work ‘The Weaver’, made by Jenny in 2015 (figure 2) combines craftsmanship and art in an almost metaphorical way.

In the beginning of the twentieth century, modern artists such as Salvador Dali and Pablo Picasso rediscovered the possibilities tapestries had to offer to nourish their creativity. They discovered – just like Jenny – the secret of a good tapestry. The combination of an intense story, a creative. well- thought out and elaborate design and a perfect execution by someone who has mastered the craft of weaving to perfection.

Drs Hélène J. Bremer, art historian and curator

Suggestions for further reading on the history of tapestry:

F.P. Thomson, Tapestry, Mirror of History, London 1980

E. Hartkamp-Jonxis, H. Smit, European tapestries in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam 2004

1 With thanks to Hillie Smit, Corpus Wandtapijten in the Netherlands, for looking at the description of the tapestry in Ammersoyen castle.

2 Jenny works with the family business Flanders Tapestries in Wielsbeke in België

About comfort, hope and miracle

Rebecca Nelemans

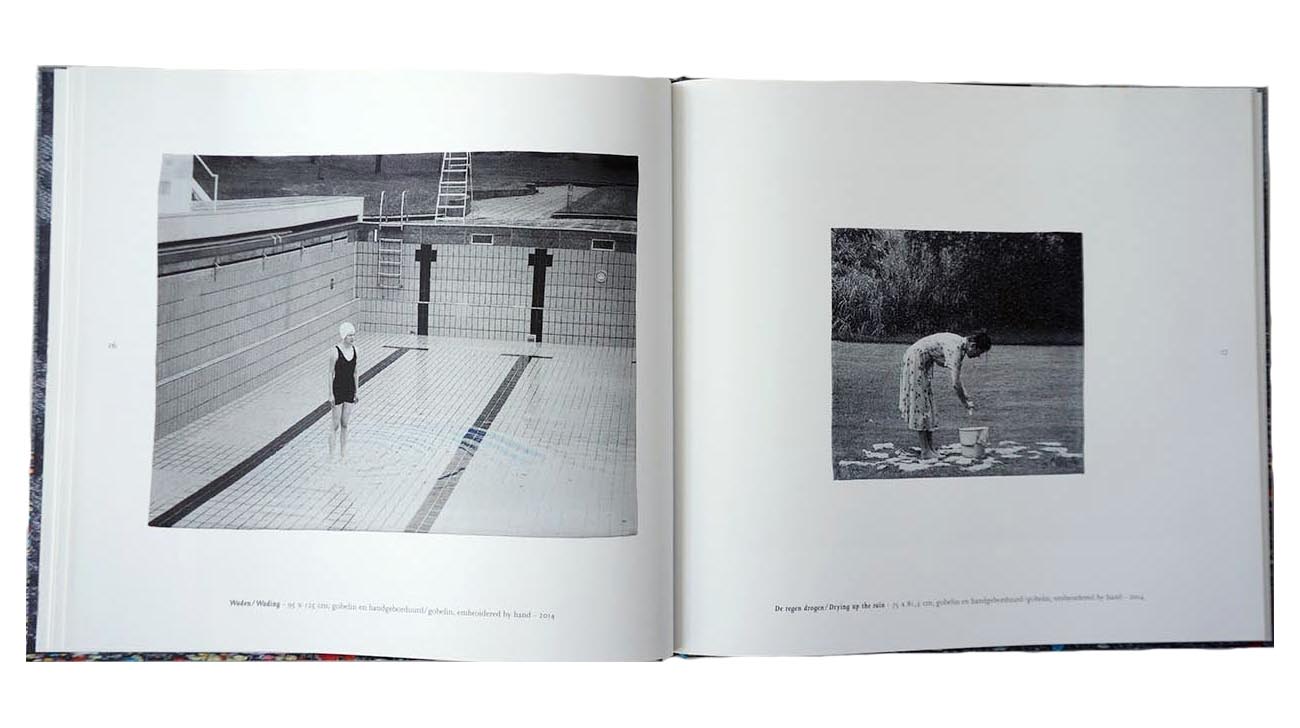

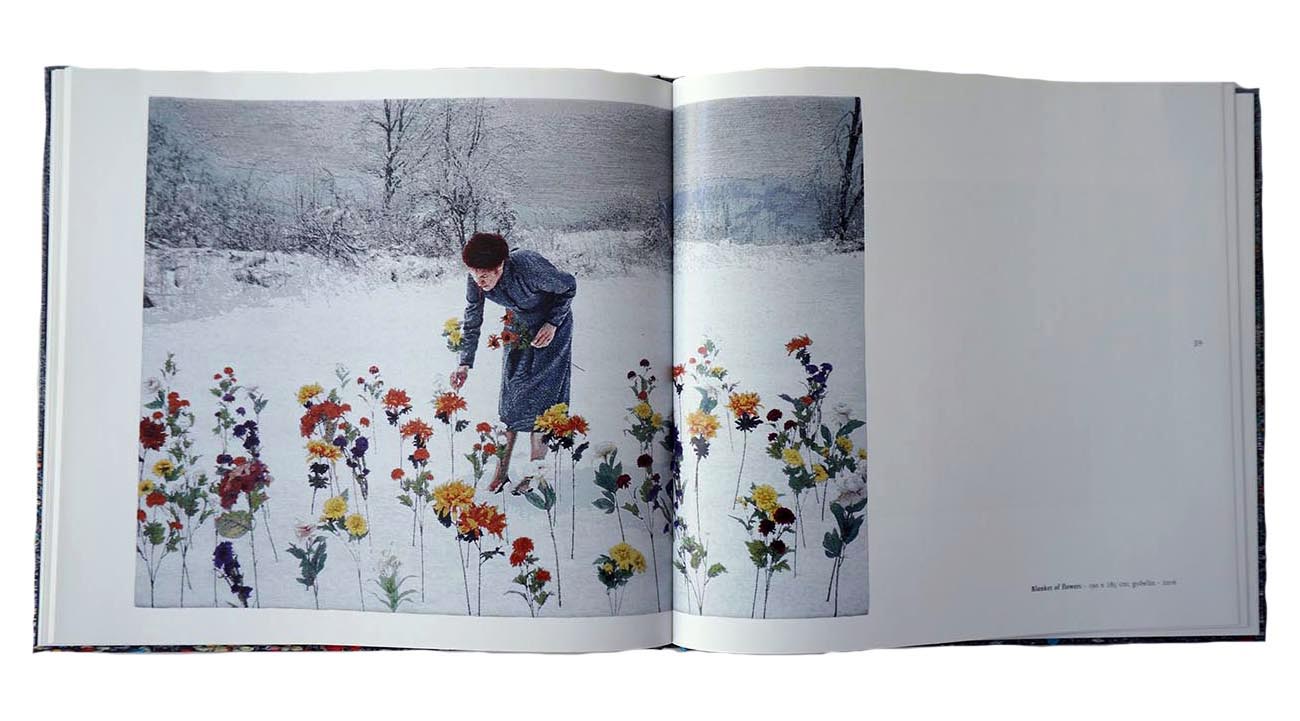

A woman in a petrol grey dress stands in a frosty landscape. In the background you see the lacework of bare winter trees, their branches white with frost. A touch of cool blue breaches the otherwise white sky. Up to this point, the tapestry Blanket of Flowers (2016) by Jenny Ymker (Zevenhuizen, 1969) evokes associations with the German Romantic landscapes by an artist like Casper David Friedrich. But in the foreground, something completely different is going on – something that breathes the atmosphere of the English pre-Raphaelites: the woman is planting bright-coloured, long-stemmed flowers into the snow. Or is she picking them? Her hand – clearly turned red with cold – clasps the stem with the same loving attention shown by the angel in Simone Martini’s Annunciation from 1333 clasping the white lily. This tapestry, too, is a hopeful and therefore comforting work, even though you can’t tell exactly what is happening.

Ymker has her gobelins manufactured by a family business in Wielsbeke in Belgium, which is small but famous for the tapestries they make for artists including Grayson Perry, Craigie Horsfield, Viktor & Rolf and Damien Hirst. The photos on which the tapestries are based she made herself. Like Cindy Sherman,Jeff Wall and Gregory Crewdson, she stages a situation to make these photos, creating her own world. For this, she seeks out locations and collects clothes and props. She always plays the leading role herself. The entire trajectory from idea via location, staging, posing, taking photographs to having the tapestries woven, is perfected with embroidery applied to the gobelins. Hundreds of hours of work go into her most recent works this way: a statement by the artist against the rat race of everyday life. She counters volatility with attention, commitment and time, lots of time.

From her earliest work – Jenny Ymker first studied ceramics and later sculpture at the Academy in Kampen – man is alone in her work: as a porcelain doll waiting in a box, ready to be played with, but by what or whom? As a young woman in a summer dress and barefoot in a snowy Swedish landscape. Or locked in a glass cage as a flower picker, picking a flower that shows a striking resemblance to the embroidered flowers on her dress. After these images, in 2012 the so-called embroidery paintings followed: small canvases to which Ymker applied a drawing which she subsequently embroidered in various colours of yarn.

At first sight, these situations are reminiscent of the lonely women in the works of American painter Edward Hopper: peeling onions or waiting at a small table. In all these works, as in the gobelins she has created since 2013, alienation plays an important role, with people seemingly alone and lost in space and time. ‘Sometimes acceleration is needed, but much more often endless deceleration, in order to capture the strange and rarely regular beating rhythm of life. Creating means mocking the monotonous ticking of the clock…’, wrote philosopher and art critic Joke Hermsen about the creative process of writers and artists.i And indeed, the tranquil scenes Ymker presents us, through clothing and props and in their choice of location seem to take place in a parallel universe where times plays a different role. The girls in her works are often precocious, the elderly women behave like children. In that sense you can consider her work a struggle with transience, with the impossible awareness of our own mortality.

And every time there is this protagonist facing away from the viewer, her face hidden in the shadow and unrecognizable as a result. The protagonist is unidentifiable, like the angel in Albrecht Dürer’s world famous engraving Melencolia I from 1514. It is always Ymker herself, but at the same time it is also the notable absentee: the mother she has missed since adolescence, the elderly people suffering from dementia she worked with for years as a creative therapist, the girl she was, the woman she is. As an artist, she has the courage to remain so close to her own story that the story captured in images becomes ambiguous and universal. In a work such as The Weaver (2015), for instance, we recognize the moment when someone loses control, when the fabric literally slips through her hands. It is an image that contradicts the optimistic image of the makeable human being in our neoliberal society. In Mopping (2016) we see the despondency, the hopelessness of our actions, a feeling we all have every once in a while.

Thus, in the end it is ourselves we see in Ymker’s gobelins: with all our powerlessness, our pain of existence, all our desires and all our hope. As if Jenny wants to assure us of what the mother in the movie Little children tells her perverted son: ‘You are a miracle. We are all miracles. Do you know why? Because as human beings we do our things from day to day and all the time we know, all of us know, that the things we love, the people we love can be taken from us at any given moment. We live with that knowledge and still we carry on. Animals don’t do that.’ii For however pointless it all may seem sometimes, a few branches in Mopping are already sticking out of the water. And the woman standing alone in a party room in one of her most recent gobelins is surrounded almost soothingly by a shower of confetti, like the divine light in Piero della Francesca’s Vision of Constantine (1452-1466), coming from above.

1 Joke Hermsen in: Melancholie van de onrust, Stichting maand van de filosofie, 2017;

2 Little Children is an American drama film from 2006 directed by Todd Field. It was based on the novel with the same title by Tom Perrotta.